Delvendahl Martin Architects

Resdiual Domains – Regent's Canal

2011

This year saw the continuation of an informal study that started the previous year, exploring the potential of interstitial sites that are a result of major pieces of infrastructure cutting through the existing city grain. Incisions made by bridges, viaducts, overpasses and rail tracks invariably generate leftover spaces that are difficult to conceive as usable due to issues of ownership, maintenance or physical constraints. But on closer inspection and especially when located within regions of urban intensity, these stretches of void activity can be seen as opportunities to re-establish relationships long severed or establishing new ones by taking

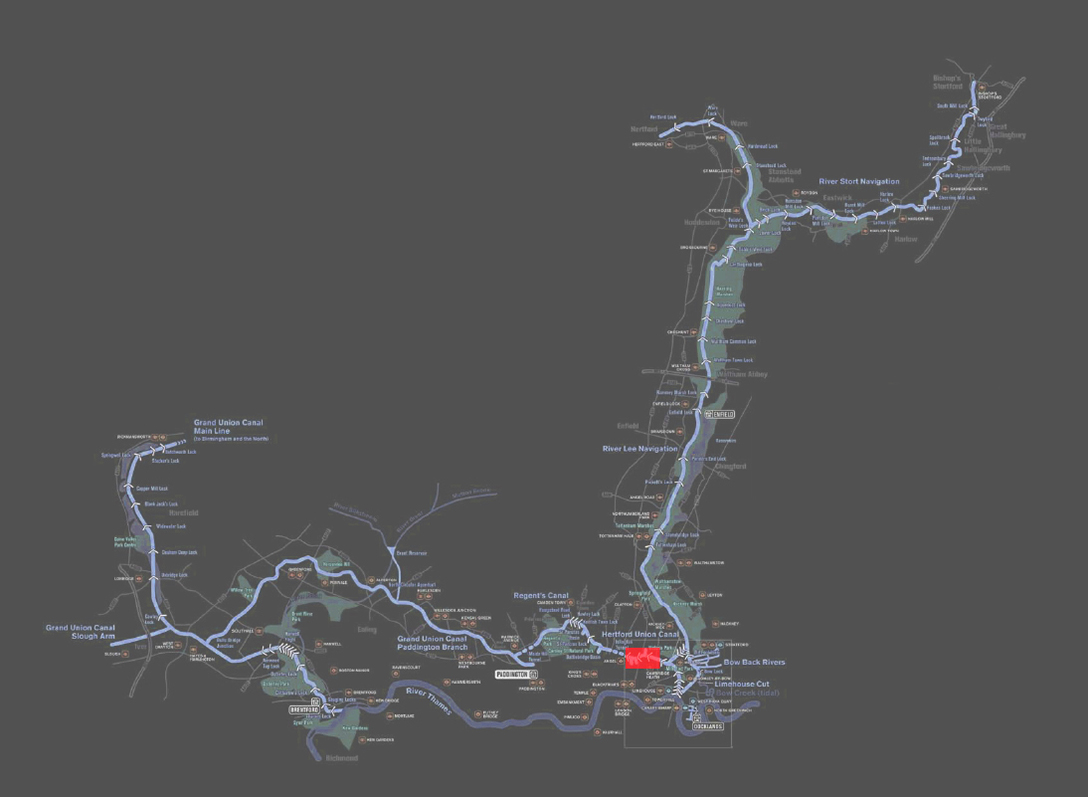

advantage of the confluent nature of this circumstances where two or more systems meet at one point. This year we chose Regent’s Canal as both the area of study and infrastructure.

The Canals

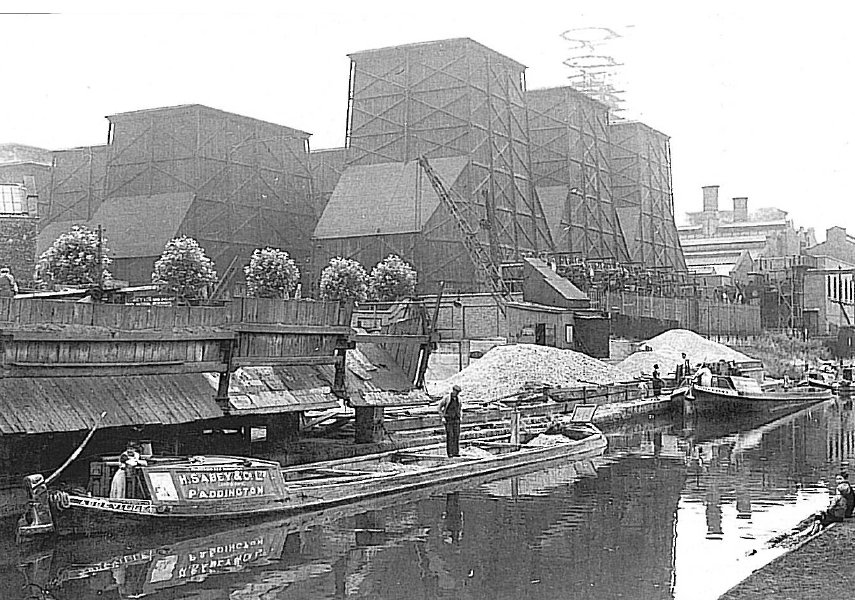

Britain’s canal network saw its heyday in the early stages of the industrial revolution before the advent of trains and road vehicles. After a period of forced decline it has found new life as a countrywide amenity generating an interest that has expanded beyond boating enthusiasts, offering a growing range of uses from cycling routes to wildlife observation spots. The continuous waterfront resulting from the pass of canals through urban areas has also established a unique relation with the facing buildings inducing neighbourhoods with a particular sense of identity. The original significance of the canal as a supply route located in the ‘back’ of servicing goods yards and warehouses, has gradually been inverted so the desirable aspect is now towards the water. The rediscovery

of the canals as an amenity has seen large areas formerly regarded as leftover spaces transformed into prime and mainly residential urban locations.

London’s Regent’s Canal is a good example of this ongoing phenomenon. Built during the 19th Century to transport cargo from sea-faring vessels to the heart of the city, it constitutes the main east/west waterway linking Paddington to the Thames via the Limehouse basin. This means that as it finds its way through different boroughs, it literally creates an urban cross-section that reveals a wide range of socio-economic geographies. We concentrated on the Hackney section of the canal, where the impact of regeneration hasn’t been widely felt and the area still maintains a fair amount of its industrial character. It is also located within one of East London’s most culturally varied communities.